Supreme Court Clarifies "Entitle[ment] to" SSI

During June and July, the legal world spends a lot of time reflecting on Supreme Court cases from the past term. It has been six years since the Supreme Court addressed an issue directly concerning Social Security disability claims (we're proud that Rebecca's previous firm, despite its usual high-dollar clientele, represented the claimant in that dispute: Biestek v. Berryhill, 139 S. Ct. 1148 (2019)).

The Supreme Court did decide one case this year, however, that is at least tangentially related to Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits: Advocate Christ Medical Center v. Kennedy, 145 S. Ct. 1262 (2025). We figured that we'd write a short blog post on the case.

We should clarify that Advocate v. Kennedy shouldn't directly apply to people applying for SSI. It should only matter to hospitals and their reimbursement rates. But, nonetheless, like most lawyers, we like to opine on Supreme Court cases. (Another attorney at our firm, Zachary, interned at the Supreme Court, and he clerked for a judge who joined the lower court decision in the case discussed below.)

The Dispute in Advocate v. Kennedy

Under federal law, hospitals that serve a “disproportionate share” of low-income patients are entitled to extra Medicare payments. To simplify greatly, the hospitals receive additional payment when they treat a sufficient proportion of patients "entitled to" SSI benefits.

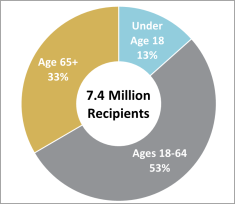

SSI is a program that provides monthly cash payments to elderly, blind, or disabled people with limited income and resources. But not everyone enrolled in the SSI program receives a payment every month—some SSI recipients may temporarily have too much money to qualify. We sometimes hear from old clients, for example, who don't receive SSI during months when they receive an inheritance.

The dispute concerned whether someone is considered "entitled to" SSI benefits during months in which they are enrolled in the SSI program but do not receive cash benefits. If those people are "entitled to" SSI during those temporary months when they don't receive benefits, then the hospitals should have received greater reimbursement from the Medicare program.

The Supreme Court’s Decision

In a 7-2 decision written by Justice Barrett, the Court ruled that someone is only "entitled to" SSI during months when they receive cash benefits. The Court relied on a few laws to make this decision.

First, the Court emphasizes that the SSI program is primarily a cash benefit program. 42 U.S.C. §§ 1381–1383generally define the conditions under which someone will qualify for SSI, and those statutes refer to "paid benefits" or benefits "to be paid." In other words, the statute that created SSI fundamentally describes SSI as a program that pays benefits. Therefore, the Court reasons, someone is "entitled to" SSI when they receive SSI cash benefits.

Second, the Court notes that other statutes refer to SSI as a "cash benefit" paid to eligible enrollees, and that eligibility is considered on a monthly basis.

Perhaps importantly, the Court also relied on its decision in Empire Health Foundation v. Becerra, which held that "entitled to" and "eligible for" benefits are effectively synonymous in the context of Medicare calculations. Even if someone is enrolled in the SSI program, therefore, the Court found that they are not entitled (or eligible) for SSI benefits during months when they are precluded from cash benefits.

Justice Jackson, joined by Justice Sotomayor, dissented. Justice Jackson emphasized that the Medicare statute used SSI entitlement as a proxy to increase reimbursement for hospitals that served poorer populations. Moreover, Justice Jackson notes that SSI enrollment ensures general monthly stability; even if someone has more resources during a particular month, the enrollment ensures general baseline subsistence.

The majority rejects these arguments. First, the Court notes that even if SSI provides ongoing security, it assesses cash benefits on a monthly basis. Second, the Court rejects an argument--more emphasized by the hospitals than by Justice Jackson--that SSI enrollment also provides "entitle[ment] to" other non-cash benefits, including vocational rehabilitation services and Medicaid.

Was the Supreme Court Right?

I don't have a strong opinion about the case. We're Social Security disability lawyers, which includes representing Supplemental Security Income claimants. But Advocate v. Kennedy fundamentally concerns how to interpret a Medicare statute, albeit one that refers to SSI.

As a general gut-check, the Supreme Court reaches a sensible conclusion: We would more normally say that someone is "entitled to" SSI during months when they are actually receiving SSI benefits. After reading the decision, frankly, I think that this case turns more on the statutory text than the majority or dissent acknowledge: If we are asking whether someone is "entitled to" SSI, we are probably asking whether the word entitled means something more like "eligibility to receive the SSI benefits" or "enrollment in the SSI program." While the opinions both cite precedents about what entitlement entails, I think there is probably more to assess there. The hospitals make a compelling argument, for example, that someone is "entitled to" SSI when they receive other non-cash benefits (such as Medicaid) through their SSI enrollment.

How the Supreme Court's Decision Matters for Social Security Disability Applicants

We still want to emphasize a takeaway for Social Security disability applicants: It generally makes sense to apply for both SSDI and SSI.

Advocate v. Kennedy addresses people enrolled in SSI who do not receive any SSI payments. Some people are approved for both SSDI and SSI, and they don't receive any SSI payments because their SSDI payments are sufficiently high to make them ineligible for SSI. But even people who do not receive any SSI payments could still benefit from SSI enrollment through other non-cash benefits.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this blog is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reading this blog does not create an attorney-client relationship. For advice specific to your situation, please contact Donoff & Lutz, LLC directly to speak with an attorney.