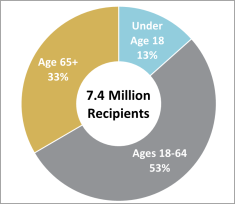

Who Is Eligible for Social Security Disability?

To receive Social Security Disability benefits, you must meet both medical and non-medical requirements.

We are regularly asked, “Am I eligible for Social Security Disability?” The Social Security disability rules may seem overwhelming at first, but eligibility for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) or Supplemental Security Income (SSI) generally comes down to two main factors: non-medical eligibility and medical disability requirements. This post explains the basic eligibility rules so you can understand what the Social Security Administration (SSA) looks for when deciding claims.

Non-Medical Eligibility Requirements

Before the SSA even looks at your medical records, they check whether you meet certain non-medical criteria. The rules differ significantly depending on the program. Below are the are explanations of the two most common programs: SSDI and SSI. There are other programs that apply to more specific scenarios with other non-medical requirements, such as Disabled Adult Child benefits and surviving spouse benefits that are not discussed here. Keep in mind you may be eligible for more than one program, and you can apply for multiple programs at the same time.

SSDI: Work Credits

To qualify for SSDI, a worker must be both “fully insured” and “disability insured.” This simply means that eligibility turns on work history: you must have worked, and paid into Social Security, both long enough and recently enough.

Americans earn work credits by paying Social Security taxes through wages or self-employment, up to four credits per year. In 2025, you earn one credit for every $1,810 earned. So, after earning $7,240 you will receive the maximum four annual credits.

Older adults need 40 work credits (about 10 years of work) for fully insured status—the same number required for retirement benefits. Younger workers may qualify with fewer: generally one credit for each year between turning 21 and becoming disabled, with a minimum of six credits.

Disability insured status also requires recent work. Usually, you must have worked at least five of the last ten years before becoming disabled. Younger workers may qualify with fewer credits.

In short, SSDI functions like private insurance programs: you’re eligible because you paid into the system.

SSI: Low Income, Low Assets

Unlike SSDI, your work history does not matter for SSI eligibility. SSI is a need-based program where eligibility turns on financial circumstances.

In 2025, a worker can earn up to $2,019 per month and still qualify for SSI, though benefits are reduced as income increases. Unearned income, like family support, can reduce or eliminate eligibility at even lower amounts. For example, if someone receives $500 a month in financial help from friends or relatives, that amount counts against SSI eligibility.

SSI also has asset limits. Countable resources must not exceed $2,000 for an individual or $3,000 for a couple. Resources include bank accounts, cash, or property other than your home. Certain assets, such as your primary residence or first vehicle, do not count toward the resource calculation.

Citizenship and Residency

Both SSDI and SSI require that you are a U.S. citizen or fall into specific categories of non-citizens. Beneficiaries generally must reside in the United States or certain territories. If you are not a U.S. citizen living in the United States, consult an attorney experienced in these cases.

Medical Disability Requirements

In addition to the above non-medical criteria, the SSA evaluates whether you are medically disabled.

Under the Social Security Act, “disability” is typically defined as the inability to work full-time for at least one year. More technically, disability is defined as the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity due to a medically determinable physical or mental impairment that is expected to result in death or has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of at least 12 months.

To determine whether someone is disabled, the Social Security Administration uses a well-established five-step sequential evaluation process.

Step One: Substantial Gainful Activity

At the first step, the SSA asks whether someone is engaging in substantial gainful activity (SGA). In concept, the SSA is asking someone is currently working. If you’re working, you’re not disabled, because disability is defined by inability to work.

In most cases, the agency asks whether you are making more or less per month than the presumptive SGA level. In 2025, the SGA level is $1,620 per month, pre-tax. If someone earns more than that, they probably aren’t disabled. If they earn less, then the sequential process probably continues.

There are some limited circumstances in which a person earning more than SGA may still be found disabled, such as if the work is accommodated. If you think that is the case, we would advise seeking the advice of an experienced attorney to assess your specific circumstances.

Step Two: Severe Impairments

The second step asks whether someone has a “severe impairment,” defined as a medical condition that interferes with basic work-related activities. If an impairment is only trivial or temporary, it will not satisfy this requirement. If the claimant lacks any severe impairments, they will be denied.

Some people miss that impairments must also meet the durational requirement—that is, that the severe impairment must last or be expected to last for twelve months or longer. Social Security disability is intended to support people with longer-term disabilities, as opposed to short-term disabilities. For example, pregnancy might cause significant functional impairments for nine months (or even a bit after that), but a pregnant woman typically won’t have twelve-month limitations that satisfy the durational requirement.

Step Three: The Listings of Impairments

The third step asks whether a condition meets or equals one of the impairments listed in the SSA’s “Blue Book.” The listings describe medical conditions that are automatically considered disabling.

It is not enough to have been diagnosed with a listed impairment. The Blue Book has very stringent functional and diagnostic criteria that a claimant must also meet. For example, it’s not enough to have chronic heart failure. But it’s nearing enough to have chronic heart failure with an ejection fraction lower than 30 percent, with three acute cardiac events in a year requiring hospitalizations. Relatively few claimants are found to meet or equal a listed impairment.

Step Four: Past Relevant Work

Fourth, the SSA considers whether you can still perform your past jobs. They compare your current limitations with the demands of your previous work. If you can do your old job, you’re not disabled.

Step Five: Adjusting to Other Work

Finally, the fifth step assesses whether you can perform any other work that exists in significant numbers in the national economy. Factors like age, education, work experience, and transferable skills are considered. At step five, things can get pretty complicated: What limitations eliminate the capacity to work? Who has skills? What is a “significant number” of jobs? What about jobs that only exist in certain regions? And the Social Security regulations—including the worn-out worker rule, the Medical-Vocational Guidelines, and the Social Security Rulings—can also direct findings of disability.

If the SSA determines you cannot reasonably adjust to other jobs, you are found disabled; if you can, the claim is denied.

“Step Six”: Drug Abuse and Alcoholism

While the Social Security Administration formally applies a five-step sequential process, in some cases one last question follows: is the disability caused by drug abuse or alcoholism? Contrary to popular myth, the Social Security Administration will deny a claim for disability benefits if the person’s impairments result from drug abuse or alcoholism.

Final Thoughts: Am I Eligible for Social Security Disability?

We hope that we’ve explained, at a high level, the eligibility requirements for Social Security disability. We want to emphasize that these explanations have been greatly simplified. But to emphasize one final point: Eligibility for Social Security Disability is not just about having a medical condition—it’s about meeting both non-medical and medical requirements. For SSDI, that means having enough work credits and being insured. For SSI, it means meeting strict income and resource limits. In either case, your condition must prevent you from working for at least 12 months. If you are unsure if you meet the non-medical or medical requirements for disability, you may want to seek the advice of a qualified attorney.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this blog is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reading this blog does not create an attorney-client relationship. For advice specific to your situation, please contact Donoff & Lutz, LLC directly to speak with an attorney.